|

Sweet

wines: an introduction to these unfashionable gems

Sadly

sweet wines have had bad PR over recent decades, and it’s now seen

as a social faux pas in many circles to admit to liking your wine in

anything other than a bone dry style. So sweet wines get a raw deal,

relegated to the end of meals accompanying dessert, or forgotten

altogether. But they’re worth discovering in their own right, and

represent some of the wine world’s most interesting, exciting and

down-right tasty gems. And they are not just for maiden aunts or

portly academics, either. Here’s my personal guide to some of the

sweet wines that are worth checking out. Sadly

sweet wines have had bad PR over recent decades, and it’s now seen

as a social faux pas in many circles to admit to liking your wine in

anything other than a bone dry style. So sweet wines get a raw deal,

relegated to the end of meals accompanying dessert, or forgotten

altogether. But they’re worth discovering in their own right, and

represent some of the wine world’s most interesting, exciting and

down-right tasty gems. And they are not just for maiden aunts or

portly academics, either. Here’s my personal guide to some of the

sweet wines that are worth checking out.

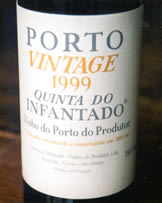

Let’s

begin with Port, possibly the world’s most famous sweet wine.

Hailing from the spectacular Douro valley in Portugal, it’s made by

stopping the fermentation of red wine part way through by the addition

of brandy, thus retaining some natural sweetness from the grapes. This

spirit addition also raises the alcohol to around 20%, which helps

preserve the wine against microbial contamination (hence the term

‘fortified’).

There

are a confusing number of Port styles and categories. It’s probably

best to avoid Ruby and Vintage Character, the cheapest styles. A step

up the quality ladder is Late Bottled Vintage (LBV): of these, I’d

recommend looking for wines labelled ‘traditional’ or

‘crusted’ LBVs, because these wines often give the character of

true Vintage Port at a fraction of the price. At the top of the tree

is Vintage Port, the top wines from particularly good vintages bottled

after just a couple of years in cask. These need long ageing (although

some people quite like them young) and will throw a thick deposit in

the bottle, so need decanting. As a slightly cheaper alternative,

Single Quinta Ports are wines from individual estates that are made in

years that haven’t been declared as vintage. They can often be just

as good, and also require decanting. Leading producers include Taylor,

Fonseca, Niepoort, Warre, Dow, Graham, Noval and Churchill. There

are a confusing number of Port styles and categories. It’s probably

best to avoid Ruby and Vintage Character, the cheapest styles. A step

up the quality ladder is Late Bottled Vintage (LBV): of these, I’d

recommend looking for wines labelled ‘traditional’ or

‘crusted’ LBVs, because these wines often give the character of

true Vintage Port at a fraction of the price. At the top of the tree

is Vintage Port, the top wines from particularly good vintages bottled

after just a couple of years in cask. These need long ageing (although

some people quite like them young) and will throw a thick deposit in

the bottle, so need decanting. As a slightly cheaper alternative,

Single Quinta Ports are wines from individual estates that are made in

years that haven’t been declared as vintage. They can often be just

as good, and also require decanting. Leading producers include Taylor,

Fonseca, Niepoort, Warre, Dow, Graham, Noval and Churchill.

In

a different style, Tawny ports are those that have been aged for a

long time in wood. With age they attain a mellow nutty, spicy

character: particularly worth seeking out are the 10 year old and 20

year old tawnies, and also the Colheitas (vintage dated Tawny wines

that are particularly popular in Portugal). As a general rule, the

longer they spend in wood, the lighter in colour they become and the

more mellow and complex the resulting wine. Port is the classic after

dinner drink, when it typically comes out with the cheese course, but

it’s also something that can be drunk alone any time.

Staying

in the Iberian peninsula but switching countries to Spain, Sherry is

another fortified wine style that’s worth getting to know. Most top

sherries are dry, but there are a few sweet styles worth

investigating. Sherries labelled Pedro Ximenez, made from air-dried

grapes, are extremely sweet and viscous with flavours of liquidized

raisins. These remarkable, unctuous wines are incredible, but won’t

be to everyone’s taste. They work well poured over ice cream.

Hidalgo, Valdespino and Gonzalez Byas make really good examples. Other

seriously tasty sweet sherries include Gonzalez Byas’ Matusalem and

Lustau’s Old East India. The great thing about sherry is that it is

undervalued, and you usually get a lot more than you pay for.

If

you like these sweet sherry styles, then you’ll probably also like

the famous Rutherglen Muscats from Australia. These are ultra-sweet,

complex raisiny wines that take on a deep brown colour from extended

ageing in casks. They’re lovely, but because they are so rich and

intense you’d probably feel as sick as a pig if you drank a whole

bottle. Perfect with rich fruit cake.

If

you want something sweet but a bit lighter, perhaps suitable for

matching with fruity desserts, then sweet muscats from the south of

France might be the answer. These are usually fresh, grapey, aromatic

wines with a lovely freshness that counteracts the sweetness well.

They’re very affordable, too. Muscat de Baumes de Venise is the most

famous, but Muscat de Frontignan, Muscat de Rivesaltes and Muscat de

St Jean de Minervois are also good.

Botrytis

is the key to the success of many of the world’s most famous sweet

wines. Also known as ‘noble rot’, Botrytis cinerea is a fungus

that under the right conditions attacks already-ripe grapes,

shrivelling them, concentrating the sweetness and acidity. The grapes

end up looking disgusting but they make profound sweet white wines, of

which Sauternes is the most famous example. The resulting wines are

sweet and quite viscous, with complex apricot, honey and spice

flavours and good balancing acidity. If you can’t stretch to good

Sauternes, then the best wines of Saussignac and Monbazillac can offer

the same sorts of flavours. I find these wines show best on their own:

most desserts overwhelm the subtleties that you are paying all your

money for.

Also

relying on botrytis for its complexity but made in a different way is

Hungary’s famous sweet wine, Tokaji. The nobly rotted grapes are

made into a paste that is then added to the base wine, adding

sweetness and flavour. Wines from Tokaji aren’t cheap, but they are

unique with complex honey, marmalade and raisiny flavours, often with

a hint of oxidation.

This

is just a brief introduction to the variety of sweet wine styles.

There are many other worthy wines that have not been mentioned here,

including the great German noble-rotted Riesling Trockenbeerenauslesen,

sweet Loire Chenin Blancs, and the rare Eisweins. My advice? Buy

yourself something sweet and give your tastebuds something they’ve

always wanted.

Back to top

|