|

The

Dirk Niepoort interview

Concerning Robustus 1990, the Douro table wine revolution and the

future for the region

Dirk Niepoort

On Saturday night (15 September 2012) I

had dinner with Dirk Niepoort at Quinta do Napoles in the Douro. It

was a lovely evening with a bunch of like-minded wine people and

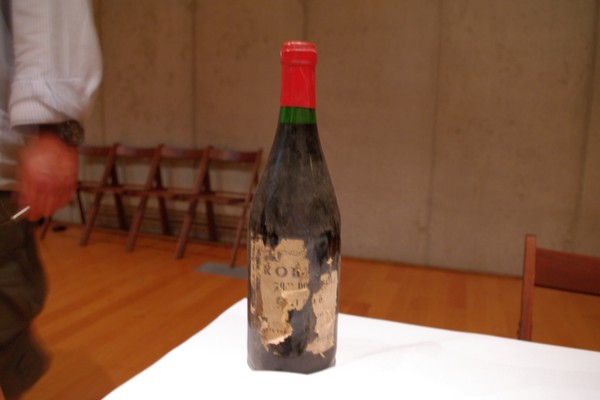

some very nice wines. Particularly special was the bottle of

Robustus 1990 that Dirk opened: the wine that was the start of his

current work with table wines from the region. I’d tasted it once

before, but here was a chance to drink it with Dirk, and ask him

some questions about Robustus and the table wine revolution that has

taken place in the Douro over the last 20 years.

Jamie Goode (JG): So this is Robustus

1990 (above). Your first table wine?

Dirk Niepoort (DN): Sort of, yes. I made

little trials before but this was the first time I made a serious

quantity. It was the first time I tried seriously to do something,

believing in the potential of the Douro.

JG: Where did the grapes from?

DN: From Carril. This is when I first

started believing that north-facing vineyards make sense. It is a

vineyard that then was 60–70 years old, north facing, with mixed

planting. It was made under bad conditions. At the time I didn’t

have money. I designed some stainless steel tanks to avoid having

legs, to make them as cheap as possible. At the time, the idea was

extracting a lot. This is actually a wine that was quite extracted.

I recently thought about this. When I was in California someone

asked me if I would go back to Portugal and make wine. I said yes, I

will be making Port. Yes, but will you be making wine? I said yes,

probably, it makes sense. So what kind of wine will you be making? I

said that I think my first wine is going to be a monster, but 20

years down the road I think I will be making fine wine. This person

said, if you think you are going to be making fine wine, why don’t

you just make fine wine. I said, because I haven’t a clue what

fine wine is, I don’t understand it, and I surely don’t know how

to make a fine. It is interesting: this was a monster, but it has

turned out quite alright. This makes me think that with all this

talk we have that we want to make elegant harmonious wine, maybe

there are other ways of doing wine that result in good wine. This

wine was quite nasty when it was young. It was very tannic. I took

it as a barrel sample to a tasting, and everyone laughed at me and

said that the wine is uncommercial, undrinkable, unsellable and un-

eveything. We kept this for four years in old wood, and then the

good news is because no one liked it, I was afraid of showing it to

people, so I said to my cellarmaster we will bottle it and when my

son Daniel is 18 he can do whatever he wants with it. Actually, I

told this recently to a bunch of people and he was in the crowd. So

after the speech he came and said, ‘Dad, where is my wine?’ I

said, ‘what do you mean, “my wine”?’

‘You just said 1990 Robustus is my wine, I am over 18

now.’ ‘I just said it.’ ‘I have some witnesses: where are

the bottles?’ It is amazing. Every bottle is good. The wine seems

to be getting better and better with age.

JG: So the following vintage 1991 you

made your first Redoma.

DN: This was made in a similar way, but

much shorter ageing. But this is also showing very nicely.

JG: So you have a long history now of

making table wines in the Douro. It seems the whole scene has been a

revolution. It is an old region with these new wines.

DN: I like to say we have 2000 years of

making bad wine, except for the Port, of course. We have a long

history, but it looks to me that everyone was concentrating on the

Ports. By having one priority, you made the Port first, and then

made the table wines with the leftovers. This doesn’t work. You

really have to focus on two things at the same time. If necessary

you have to have two wineries. You need two teams, if necessary. I

am exaggerating. But you have to respect the vineyards and picking

times for each.

JG: Of the Douro boys, you are alone in

being equally serious about Port and table wines. Do you think the

two can coexist happily?

DN: I don’t even believe in it, I am

totally convinced that the future of the Douro has to go through

three priorities at the same time: the Port, the table wine (be it

white or red), and also the tourism. If we play the game well on the

three we can only win. Then, for the growers, the future is bright.

I think the first thing we have to stop is this fighting about

whether the wine is better or more important than the Port. On top

of that, for me there is no doubt that the best vineyards for Port

are clearly not as good for table wine. Port likes special

conditions. It likes exaggerated conditions: too much heat, dry

conditions. For great Ports the vineyards just stop the maturation

because it is too dry and hot, and then a little bit of humidity

makes the sugars go up and the acidity down. Acidity is my fetish

and the thing I believe most in, but for Port it is not as

important. For white and red wine, I have no doubt that the key

element is acidity, which is not something that we have in

abundance, so we have to find ways to keep this acidity. This is

where the Douro is special. It is 45 000 hectares. It is huge. It is

not like most vineyards where you have south/east/west expositions.

We have north, east, south, everythingf. It is not 100–200 m

height; here we are talking about 80–800 metres. And we are not

talking about one, two or three varieties—we are talking about 85

varieties. It is a complicated matter. But I will change the word

‘complicated’ to ‘complex’. We have to do what we have done

for Port: we have to understand which are the vineyards for Port,

which we know, and now we have to find out what we can do with the

rest of the vineyards and what is the true potential for making

great wine. Everyone laughs at me because I like these very high

vineyards. Yes, they are always greener than the other ones, but it

is a question of waiting, of patience. Because it is so hot,

sometimes it is important to pick the high vineyards a little bit

earlier, may be even a bit greener, and blend it. Therefore you

don’t have to make acid corrections and you have lightness and

elegance. The future is very bright. When I started making Robustus

it was a revolution and I was alone, more or less. Joăo

Nicolau de Almeida started about the same time, and Gaivosa did.

Slowly some others started. Then the second revolution came in

2000/2001, when suddenly there was a bunch of people really going

for it. Now it is easy and no one questions making wine in the Douro,

except for one Port house. It is probably the most famous area of

Portugal at the moment and it will probably grow in the future.

JG: As well as the red table wines, you

have been quite a pioneer of whites. Do you think these have an

important future in the Douro?

DN: It is obvious. When I started I was

the only one; now I have many colleagues making very good wines. 20

years ago no one really talked about white wines: we drank Vinho

Verde and not much more. Now white wines are a big thing. It is

totally linked to the quality of the wines. These have increased in

quality and there is a positive evolution. There is a lot to learn,

but the future is bright.

JG: So what was it that enabled this

table wine revolution to happen?

DN: I think globalization is a negative

thing, but it has a positive side. People are travelling a lot more.

Portugal was a really closed country, economically and politically

speaking. It was difficult to go out and come in. It was very poor.

The fact that people are travelling more and people see more through

the internet makes a huge difference. It is not technology. It is

also technology, but I think technology is becoming a problem.

Portugal is in a similar situation to South Africa. Both countries

went from making some great wines but mostly rustic, old fashioned,

oxidative wines, and they jumped from this extreme to the other,

which is making highly technological wines. I like to call these

castrated wines because they all taste the same; they are fruit

driven; they are made with all sorts of chemicals. This is bad.

Portugal needs to respect traditions more, and the local varieties.

We should be happy to be in Portugal because this is a hidden

treasure. We have old vines and all these varieties. We are probably

the richest country in the world in terms of varieties and terroir.

It is amazing how small Portugal is and how many different terroirs

we have. You can go 20 miles east, west, north or south and suddenly

you move from schist to granite to calcareous soils. You don’t

find this anywhere else. There is a new generation who have studied,

which is a good thing, but it tends to be a generation who only do

what they studied. There is something missing: the hearts; the love

for the wine. There is a great potential to grow in a positive way.

See

also:

Dirk

Niepoort retrospective Dirk

Niepoort retrospective

Find these wines with wine-searcher.com

Back

to top

|