Bretty Beaujolais

Time to crack another of my 'natural' wines, which I purchased on a recent Paris trip. Now, although I'm a wine technology sort of guy, I'm not a wine faults policeman. The initial response of those who have learned to spot what are known as wine faults is to then police wines they taste for the faintest whiff of brettanomyces, or volatile acidity, or reduction. I prefer to treat each wine on its own merits, and judge more holistically. I can forgive a 'fault' if it works in the context of the wine. This bottle has left me struggling a little: I don't think brettanomyces works terribly well in the context of a Cru Beaujolais. Of course, I don't have a lab test to prove the presence of brett, but this is about a bretty a wine (to my perception) that I have met. It's a shame: I wanted to love it.

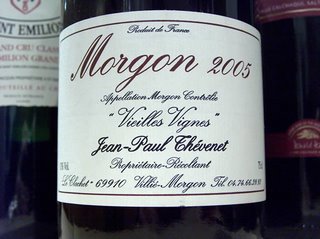

Time to crack another of my 'natural' wines, which I purchased on a recent Paris trip. Now, although I'm a wine technology sort of guy, I'm not a wine faults policeman. The initial response of those who have learned to spot what are known as wine faults is to then police wines they taste for the faintest whiff of brettanomyces, or volatile acidity, or reduction. I prefer to treat each wine on its own merits, and judge more holistically. I can forgive a 'fault' if it works in the context of the wine. This bottle has left me struggling a little: I don't think brettanomyces works terribly well in the context of a Cru Beaujolais. Of course, I don't have a lab test to prove the presence of brett, but this is about a bretty a wine (to my perception) that I have met. It's a shame: I wanted to love it.Jean-Paul Thevenet Morgon Vieilles Vignes 2005 Beaujolais, France

Hmmm, bretty Beaujolais. Quite fresh, brightly fruited nose with a spicy, medicinal, smoky sort of character. The palate has a meaty, spicy, phenolic character imprinted on the otherwise pure red fruits. Quite enjoyable in a very savoury, spicy, funky sort of way, but it's verging on flawed for me, and I don't really mind brettanomyces too much in the right sort of context. Very good+ 85/100

Hmmm, bretty Beaujolais. Quite fresh, brightly fruited nose with a spicy, medicinal, smoky sort of character. The palate has a meaty, spicy, phenolic character imprinted on the otherwise pure red fruits. Quite enjoyable in a very savoury, spicy, funky sort of way, but it's verging on flawed for me, and I don't really mind brettanomyces too much in the right sort of context. Very good+ 85/100

Labels: beaujolais, brettanomyces, France, morgon, natural wine

2 Comments:

Thevenet is renowned for his "no-sulphur" approach to wine-making which would create the conditions for brett to flourish. One imagines that 05 with its extra phenolics would be, by definition, a brettier vintage.

I think brett is still a murky subject. The more technical winemakers are appalled by its presence as they looking for specific flavour profiles in their wines and understandably desire to have as much control over the vinification process as possible. Hence the big doses of sulphur at crushing. Yet some of the most critically acclaimed wines (one thinks of many examples: Beaucastel (in particular), many grand cru classe Bordeaux wines in the 80s, Loire reds from 97, Provence reds from 99, great wines from Priorat, legendary Aussie Shiraz, have been affected by brett; are we saying, in hindsight, that these wines were all spoiled or, at the very least, highly compromised? And what about Grange and its volatile acidity? Or the oxidised wines of Jura? Or the accident that is Palo Cortado? There has to be a degree of uncertainty in winemaking, and whilst brett is undesirable in quantity, if the wine can support a certain amount, then it is not necessarily a bad thing. I'm sure the wines of Bandol have a bretty signature, but I love the flavour and I would guess others do as well.

Having said all that I would add the caveat that certain wines don't carry brett very well. I'm thinking Gamay and Pinot Noir, in particular.

One of the major debates in the next few years will be about "natural wine" and interventions in the winery. On the one hand you have those who believe that true wine should only be made with wild yeast, that fermentation must be natural & without aids, that there should be no interference with the natural concentration of grapes and no modifications such as acidification or chaptalisation, no filtering and no fining should take place and little or no use of sulphur. On the other hand there will be those who, whilst they subscribe to some or many of the above ideals, believe in eliminating any factors which might cause variability or potential bacterial spoilage and that the winemaking process should always be determined by scientific analysis and evaluation. The two views are relatively divergent philosophically rather than utterly opposing scientifically, and the reason why we can still celebrate diversity in wines is because winemakers are rarely totally interventionist or totally non-interventionist - they can choose what to do or what not to do and accordingly make "their" wine taste a particular way.

I quite agree, Doug, that there are few absolute wine 'faults', and that wine has to be judged holistically, recognizing that in certain contexts a characteristic present in a wine works, whereas in others it doesn't.

I also agree that natural wine is going to be one of the key debates in the wine world over the next few years.

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home