It is well known that context can affect our experience (and enjoyment) of wine. But how do you measure this?

In a paper published in open access scientific journal Flavour, Charles Spence, Ophelia Deroy and colleagues looked at potential crossmodal correspondences between classical music and fine wine. To put this more simply, does listening to music affect the wine drinking experience in measurable ways? [Is hearing affecting taste?]

To answer this question they took 26 wine drinkers, four rather good wines (Domaine Didier Dagueneau Pouilly Fumé Silex 2010, Domaine Ponsot Clos de la Roche 2009, Château Margaux 2004 and Château Climens 2001) and five pieces of music (Mozart Flute Quartet in D major, K285 – Movement 1, Allegro; Tchaikovsky, String Quartet No 1 in D major – Movement 2, Andante cantabile; Ravel, String Quartet in F major – Movement 1, Allegro moderato, très doux; Debussy, Syrinx; Ravel, String Quartet in F major – Movement 2, Assez vi).

They asked participants to taste the wines and rate the particular matches. They also rated the wines with and without music. And in another experiment they matched odours to different pitches of the same note.

After lots of number crunching there were some significant effects. There were specific classical music-fine wine pairings that appeared to go particularly well (or badly) together. Tchaikovsky’s String Quartet No 1 turned out to be a very good match for the Château Margaux 2004, while Mozart’s Flute Quartet in D major was found to be a good match for the Pouilly Fumé. The participants perceived the wine as tasting sweeter and enjoyed the experience more while listening to the matching music than while tasting the wine in silence.

These effects weren’t large, but they were there. And there’s so much noise in experiments like this that it’s remarkable that significant effects were pulled out. After all, music is very personal. Our liking of music is strongly influenced by our exposure to it, and our relationship with a particular type of music changes dramatically on repeated listening. Music also has the ability to tap into the emotions, but one piece of music can move one person greatly and leave another cold.

It would be fun to repeat this sort of experiment with more contemporary music, and in a situation where the music is incidental (people aren’t aware that the experiment is looking at the effect of music; they are simply asked to rate wines while music is playing in the background. You could change the music and slip duplicate wines in later in the tasting, or in a tasting on a separate occasion).

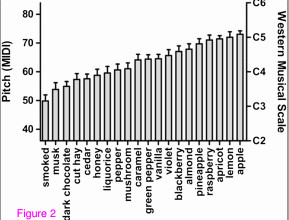

The figure above is taken from the paper, and I think it’s one of the most interesting findings from this study, looking at the association of the pitch of a note with particular aromas. Some aromas are more bass; some are more treble.

Do you think this sort of study means that wine writers should be searching for musical metaphor in their tasting notes?

7 Comments on Wine and music, a scientific study

Does the finding of an association between pitch and aroma suggest that we are all somewhere on a synaesthetic spectrum?

I can just about see how dark chocolate and smoked could be low notes, but I’m surprised to see cut hay down there. I would have thought it would be more up with the pineapples and lemons.

I wonder if the Margaux would taste like mud if one would taste it while listening to Justin Bieber. I guess I’ll never know…

A worthy exercise initially it seems, but as you alluded to at the end this is the study of what happens when two very subjective experiences occur simultaneously. As interesting as it is, with so many variables involved can it really be said to be of any real use?

This is fascinating!

I think I prefer my reds with jazz, however.

Great post! 🙂

A decent read during the Christmas hinterland.

The fact that different products (music or wine) with aesthetic attributes can match together doesn’t surprise me.

That Mozart and Pouilly Fume go together well seems pretty intuitive. In a sense with these two we are comparing 2 simple, clean, ‘attractive’ easy going products with one another (notwithstanding the relative genius of their makers). The fruity expression of the Pouilly Fume matches the easy going charm of the Mozart. It’s a question of matching like with like, as a WSET primer in food & wine matching would tell us to do.

The Tchaikovsky (no offence to him) would seem to be low-balling the classicism & complexity of the Margaux 2004 (suggested as a good match in the article). If you are taking something from this Russian musical genre and format (string quartet), then fine – no problem – but I would be picking a Shostakovich DSCH string quartet to match complexity with complexity. That would be more of a like with like match.

With the Ravel & Debussy we are going a bit haywire. Whilst these composers are part of the early 20th century French expressionist school, (thus all a bit nebulous and twee IMHO) these 2 specific pieces are pretty avant-garde and helped set the trend for the following half century or so. The equivalent of say, experimenting with wild ferments or bio-dynamics that then start to become standard practise for a trail blazing bunch of producers in a region (Heymann-Loewenstein & Van Volxem seem to be spring to my mind as example).

Not quite sure where I am going with this other than to say if (the WSET approach) you can match like with like, (e.g. complexity with complexity) then this would optimise the sensorial results.

very interesting and thanks for providing the link

I can only agree with all your comments – ie that’s there is a lot more we need to do to understand the cause of these matchings, but also to see whether we can generalise the results obtained on a ‘wine by wine and piece by piece’ basis. Are there aroma-music matching principles, or are the associations always made on different bases (sometimes because of a match in complexity, sometimes because of a match in ease, etc.).

On the synaesthetic aspect, though, it’s not clear that it is what is at stake – the specificity of synaesthetes being to have say auditory experiences when they drink wine, even in the absence of music. These matchings are much more like intuitions of congruence. And it would be great to see whether they are shared by experts and novices alike.