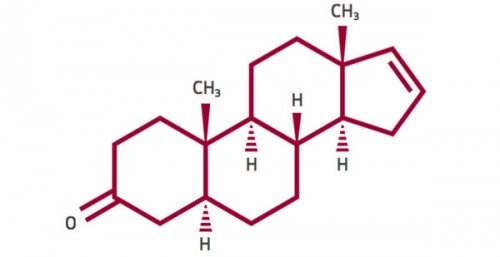

Androstenone is a smelly steroidal compound produced by pigs that is described as sweaty, urinous, and musky by those who can smell it. Depending on the version of the OR7D4 gene that you will have, you’ll experience androsterone as unpleasant, or sweet, or you might not smell it at all.

Kara Hoover and colleagues have looked at sequences for OR7D4 in 2,200 people globally, and have found that this gene has been subject to evolutionary selection. In African populations, there’s more sensitivity to androsterone, but in northern populations where pork is important in the diet, there is less. The idea is that when people began domesticating pigs, there’d be a selective advantage in finding pork palatable.

Interestingly, the insensitivity to androstenone changes though adolescence in most people. And even more interestingly, the ability to smell it can be induced by exposure. So people who can’t smell it at all, can in some cases begin to smell it after being exposed to it. This is surprising for a trait that has a strong genetic component.

How do we begin to explain this?

First of all, we are not measuring devices. There’s a lot of hidden processing that goes on in the brain before we are consciously aware of a smell or taste.

The dimensionality of the olfactory receptor space is not the same as that of the perceptual space. The receptor space consists of a set of some 400 different receptor types, the binding sites of those receptors, and the downstream signalling. This information is quite different from the perceptual space, which is influenced by evolutionary constraints: what our sense of smell needs to do for us to succeed in the world.

We don’t have conscious access to the receptor space, although it feels like we do. Think about it: why is that some molecules smell and others don’t? Is it simply because of the specific olfactory receptors that we have? Or is there a lot of information available at the receptor space that is ignored in later processing, as our brain examines the various patterns of receptor activation and extracts the useful information out of them?

Could it be that if we somehow gained access to all this receptor space, that our smell world would be very different? What if a cocktail of drugs could open up this different world for us?

In his book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Oliver Sacks told the story of a young medical student (it was actually Sacks himself it turns out) who spent a night taking speed, cocaine and PCP, and awoke to find he had a vastly heightened sense of smell. It’s a bizarre and remarkable tale, and this only lasted for a limited time, but it shows that potentially our receptor space is much bigger than our perceptual space. There’s an awful lot of smell information that our brain simply edits out, it seems. Wouldn’t it be amazing for a wine taster to have temporary access to this world?

3 Comments on Are we potentially much better at smelling than we realise? The curious case of androstenone

Maybe we need to suggest to Chris Ashton that we partake of Sacks’ cocktail of pleasures before a day at The Oval…

Is this like the performance enhancing steroid that MLB caught Mark McGwire using when he was pounding home runs? That was called ‘androstenedione.’

I’d suggest that decreased sensitivity is less to do with making pork palatable and more to do with their “farmability”. Pig manure is arguably the smelliest of all common farmyard manures, and I imagine would be a significant discouragement to the domestication of pigs.