How

wine is made

An illustrated guide to the winemaking process, by Jamie Goode

It all starts with grapes on the vine: and it's

important that these are properly ripe. Not ripe enough, or too

ripe, and the wine will suffer. The grapes as they are harvested

contain the potential of the wine: you can make a bad wine from good

grapes, but not a good wine from bad grapes.

Teams of pickers head into the vineyard. This

is the exciting time of year, and all winegrowers hope for good

weather conditions during harvest. Bad weather can ruin things

completely.

Hand-picked grapes being loaded into a half-ton

bin.

Increasingly, grapes are being machine

harvested. This is more cost-effective, and in warm regions quality

can be preserved by picking at night, when it is cooler. This is

much easier to do by machine.

The harvester plucks the grape berries off the

vine and then dumps them into bins to go to the winery. This is in

Bordeaux.

These are machine-picked grapes being sorted

for quality.

Hand-picked grapes arriving as whole bunches in

the winery.

Sorting hand-picked grapes for quality. Any

rotten or raisined grapes, along with leaves and petioles, are removed.

These sorted grapes go to a machine that

removes the stems. They may also be crushed, either just a little,

or completely.

These are the stems that the grapes have been

separated from in the destemmer.

Reception area at a small winery. Here grapes

are being loaded and then taken by conveyor belt

to a tank, from where they are being pumped into the fermentation

vessel.

This is where red wine making differs from

whites. Red wines are fermented on their skins, while white wines

are pressed, separating juice from skins, before fermentation. This

fermentation vessel - a shallow stone lagar in Portugal's Douro

region - will be filled up and then the grapes will be foot trodden,

so that the juice can extract colour and other components from the

skins.

This is a very

traditional winery, again, in the Douro. The red grapes have been

foottrodden, and fermentation has begun naturally. These men are

mixing up the skins and juice by hand: this process is carried out

many times a day to help with extraction, and also to stop bacteria

from growing on the cap of grape skins that naturally would float to

the surface.

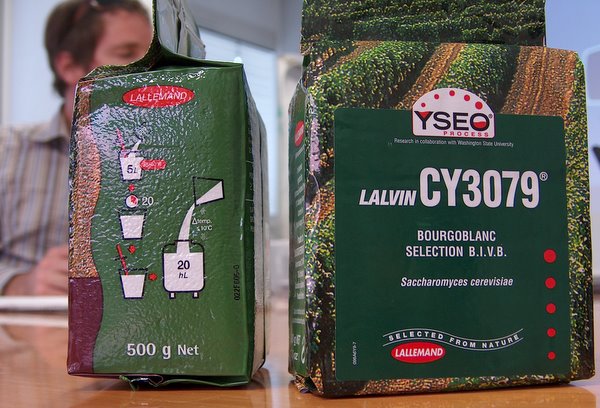

Sometimes

cultured yeasts are added in dried form, to give the winemaker more

control over the fermentation process. But many fermentations are

still carried out with wild yeasts, naturally present in the

vineyard or winery.

These red grapes

are being fermented in a stainless steel tank. During fermentation,

carbon dioxide is released so it is OK to leave the surface exposed.

Sometimes, however, fermentation takes place in closed tanks with a

vent to let the carbon dioxide escape.

In this small

tank the cap of skins is being punched down using a robotic cap

plunger. In some wineries this is done by hand, using poles.

An alternative to

punch downs is to pump wine from the bottom of the tank back over

the skins.

Here, fermenting

red wine is being pumped out of the tank, and then pumped back in

again. The idea is to introduce oxygen in the wine to help the

yeasts in their growth. At other stages in winemaking care is taken

to protect wine from oxygen, but at this stage it's needed.

Once fermentation

has finished, most red wines are then moved to barrels to complete

their maturation. Barrels come in all shapes and sizes. Above is the

most common size: 225-250 litres. The source of the oak, and whether

or not the barrel has been used previously, is important in the

effect it has on the developing wine.

This is a much

larger, older barrel, imparting virtually no oak character to the

wine. This suits some wine styles better than smaller barrels.

This is a basket

press: once fermentation has completed and the young wine has been

drained off the skins, the remaining skins and stems are pressed to

extract the last of the wine that they contain.

This is a bladder

press, used for some reds and almost all whites. A large bladder

fills with air, pressing the contents gently and evenly, with

gradually increasing pressure.

And this is what

is left at the end - the marc. It can be used to make compost.

The inside of a

tank that has been used to ferment white wine: the residue consists

of dead yeasts cells.

Barrel halls can

still look quite traditional. Cool underground cellars are perfect

for maturing wines - a process that takes anything from six months

to three years.

Winemakers

typically check the maturing red wine barrels at regular intervals,

and top them up as some of the wine evaporates during the maturation

process.

Occasionally it

is necessary to move wine from one barrel to another, or from barrel

to stainless steel tank. This cellar hand is using nitrogen gas to

move the wine without exposing it to large amounts of oxygen.

Here wine is

being moved from one barrel to another deliberately exposing it to

oxygen to aid in the maturation process.

Some wines see no

oak at all, but are kept in stainless steel tanks to preserve the

fresh fruity characteristics.

Finally, the wine

is ready and is prepared for bottling. Often, filtration is used to

make the wine bright and clear, and to remove any risk of microbial

spoilage. The glass on the left has been filtered; on the right you

can see what it was like just before the process.

See

also:

How

cork is made: an illustrated guide How

cork is made: an illustrated guide

Published

08/11

Back

to top

|